“My humanity is bound up in yours, for we can only be human together.” Desmond Tutu

We arrived in Cape Town, South Africa on March 18th for a 6-day visit. Of the many places we’ve traveled, South Africa’s beauty and opportunities for varied experiences is unparalleled.

“Pretty Good for ‘A Sh*thole Country’”

Our ship’s dock provided a lovely view of the iconic Table Mountain. Along with the masses, we took the cable cars up to the top; a few of the Voyagers hiked up for sunrises and sunsets. The panoramic view from this craggy perch was a highlight. As our other South Africa blog, Part I shows, other highlights included a safari at Aquila Game Reserve, with a bus ride through wine country. Also, a day’s drive down the rocky coast to Cape of Good Hope to meet some awesomely awkward penguins and see Seal Island reminded us of the beautiful Northern California coastline.

Within short walking distance from the ship, the V&A Waterfront area had fun shops, entertaining street performers, and a fancy Ferris wheel. Various restaurants had delicious and reasonably priced food, and South African wines. Many meals were like U.S. dining. A mall area had familiar and unique shops. We were able to re-stock our snacks supply from the large grocery in the mall. And, happily, we had excellent coffee at the Now Now coffeeshop. “Now Now” is a reference to “African time,” which can be unpredictable by Western standards. (Larry still misses Starbucks almost as much as we miss our reliable internet connection!)

We went to GreenMarket Square and Old Biscuit Mill Market for “cultural exchanges” (aka shopping), and the best meal of the Voyage. We meandered through Bo-Kaap, the predominantly Muslim neighborhood, with colorful houses. And, we got our green nature fix in the Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden.

Like many places in the world (including areas of the U.S.), Cape Town has high crime rates (it’s been called the “rape capital of the world”); unemployment is exceedingly high (especially for people of color); and they are facing a significant water shortage. During our visit, the city shut down parts of the grid for designated hours to save electrical power. These problems are inextricably linked with structural inequality and government corruption.

However, our engaging interport lecturer, Zubeida Jaffer, summarized it best. While acknowledging horrific history and continued challenges, she shared the nation’s many assets and successes. Throughout an evening lecture, she (with good humor) remarked that South Africa is doing “pretty good for a sh*thole country.” [Her use of this phrase references a ludicrously xenophobic comment made by the man currently occupying the U.S. presidency.]

Ms. Jaffer is a journalist, author, and activist; she was a political prisoner because of her role during the anti-apartheid movement. A significant measure of the health of a democracy is the freedom of the press. Ms. Jaffer noted that the World Press Freedom Index ranks the U.S. as #45 (irony!). South Africa is #28. As she said, indeed, “not bad for a sh*thole country.”

Stories and Re-Storying

Ms. Jaffer, and others like her, play a crucial role: Story-tellers who document our “reality” and world. As we travel, we realize at new levels the power of stories. Whose stories are told? Who stars in the stories? Whose stories remain invisible or are turned into caricatures. For example, on a grand scale, in our travels and in general, we see the dominance of His-story, i.e., Male stories. (Ms. Jaffer noted the sexism in the anti-apartheid movement, itself.)

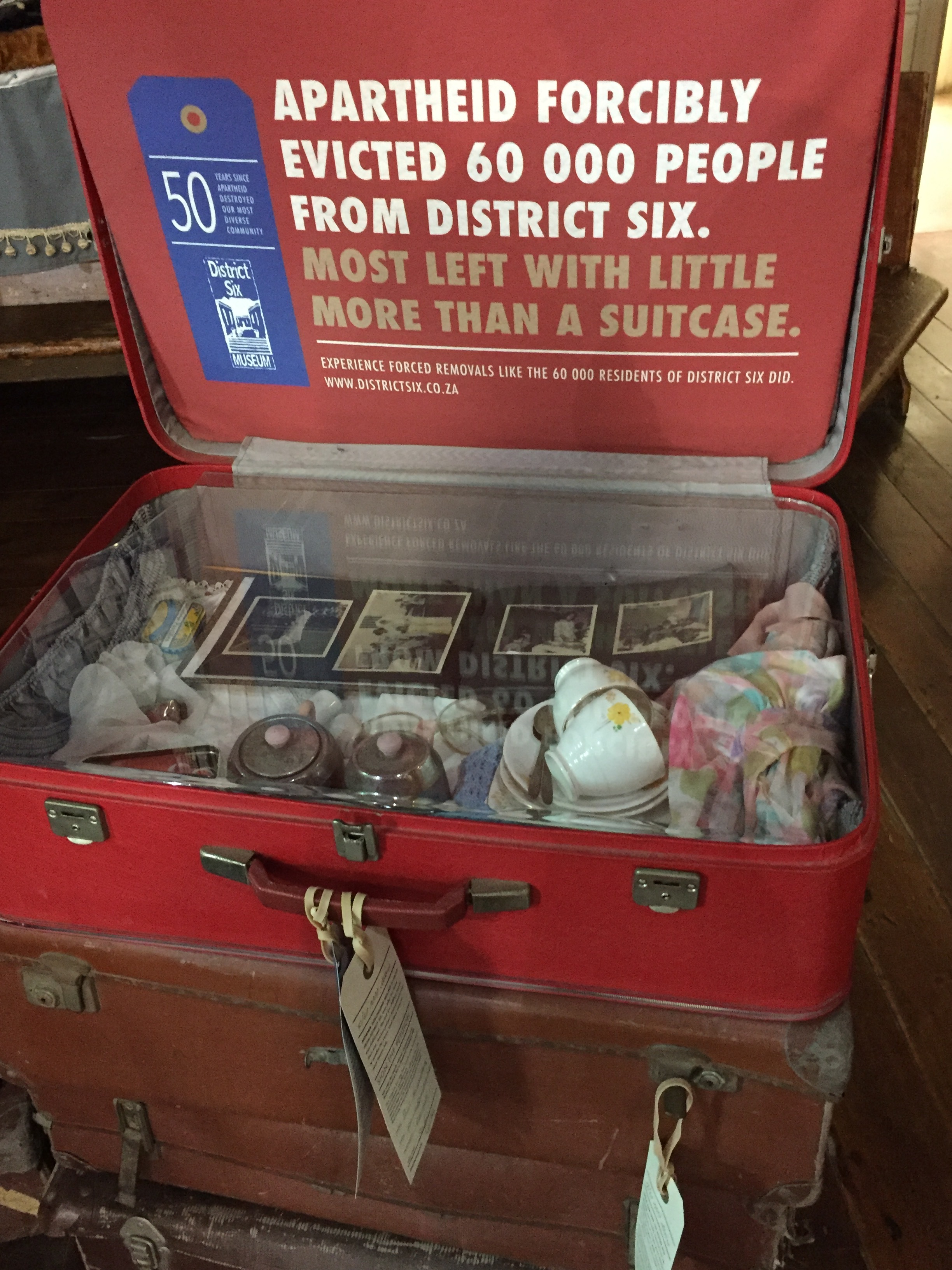

Apartheid is a prominent story-line in South Africa. This nation’s attention to the horrors of this blatant racism is notable. The stories of apartheid are told by former political prisoners and guards on Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned. Mandela’s extraordinary life story of peaceful activist, political prisoner, to elected president is well-known. We also visited District Six Museum, which uses photos, images, written accounts, and guides who lived in District Six to tell the layered, lesser-known stories of ordinary people diminished by apartheid. Numerous black families were driven from their homes through legal (and immoral) actions of apartheid.

A SAS field trip included a visit to a township. There, we had a delicious South African meal prepared by Sheila in her home. We listened to a beautifully talented local band play traditional instruments and sing in gorgeous harmony. Frankly, it was discomfiting to be part of an obviously privileged, largely white busload of people walking through this impoverished, largely black community. Poverty should not be a tourist attraction. Yet, glimpsing this economic poverty juxtaposed with cultural richness shows both the insidious legacy of apartheid and the incredible resilience of these people.

Ubuntu: I Am Because You Are

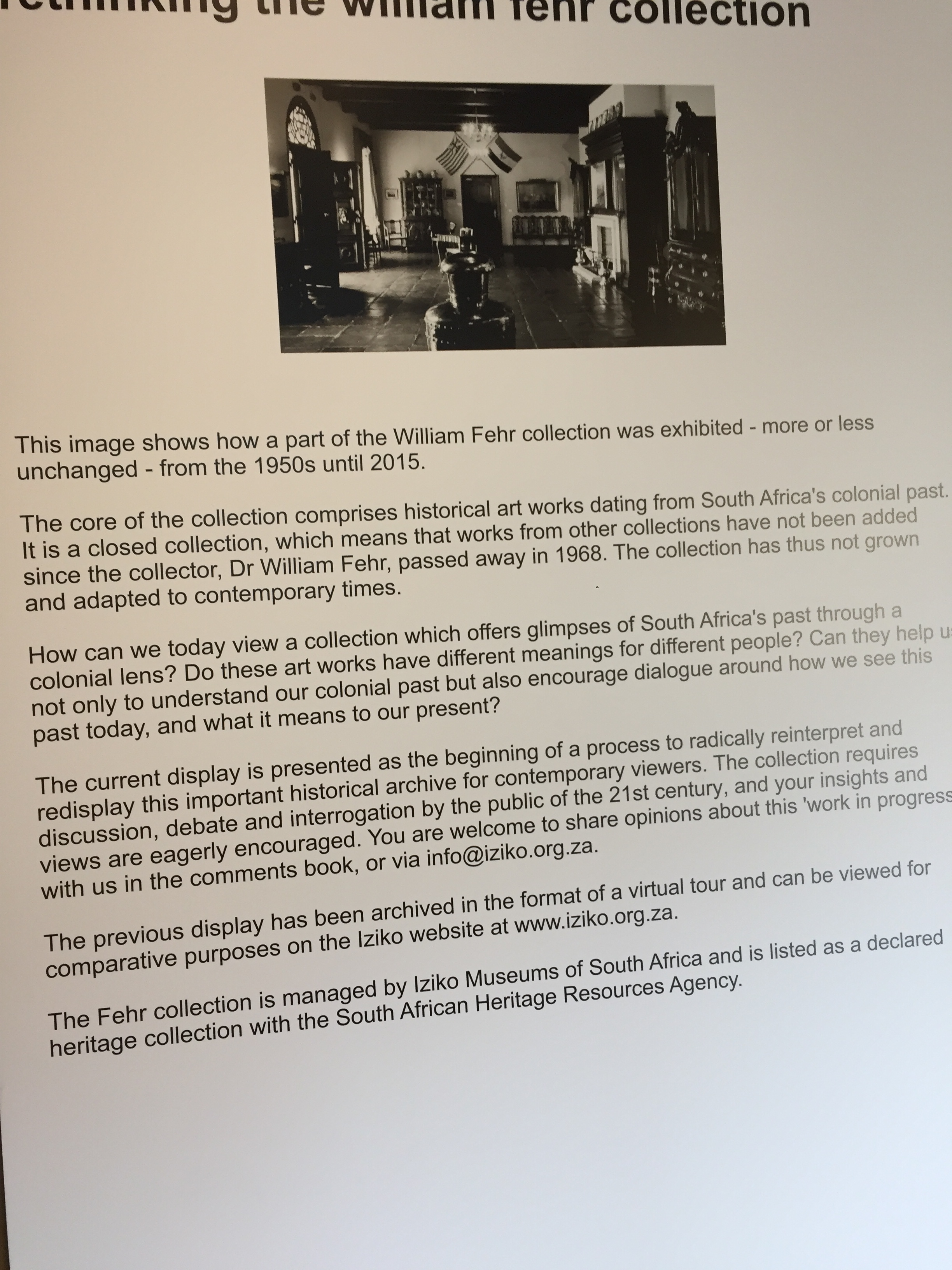

An overarching reference point in our SAS Global Studies class is Chimamanda Adiche’s brilliant TED talk The Danger of a Single Story. Art displays at the fort and Castle of Good Hope and Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa invite viewers to critically consider whose stories are being told. For instance, does the artist portray the view of the conqueror, to the further diminishment of the conquered? Does the art present a white-washed view? Again, whose stories get told and by whom?

A casual interchange with a youngish, black male security guard on the Waterfront led to this local expert telling a story of apartheid, succinctly and insightfully. He explained how whites, a miniscule minority, were able to disenfranchise the vast majority, people of color: “They played the battle of the minds, first. They pitted us against each other, invented tribalism. They provided weapons to one group to fight the other, while they benefited.” When asked about the aftermath of apartheid, he said a major issue now is land reclamation. How does a country resolve a history of stolen lands? Finally, he emphasized the danger of a single story—“People of color and whites need to get to know each other as real people.”

We have long-admired Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who sailed previously with Semester at Sea! We are saddened to hear of his declining health. We were very moved in our visit to the Desmond & Leah Tutu Foundation’s exhibition, In His Words. This display of Desmond Tutu’s writings tells a story of redemption, after incredible atrocities; a story of pursuing peace as a way forward. A Nobel Peace Prize winner, Archbishop Tutu said, “there is no peace, [without] justice.”

Tutu was the architect of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. This Commission served as a conduit for those affected by the horrors of apartheid to tell their stories and seek some closure. This process allowed those who had perpetrated the evils of apartheid to both be held accountable and be given grace when they acknowledged their role. (Notably, some, mostly upper-echelon apartheid leaders refused to participate and were sent to prison.)

One of the threads in our travels has been seeing the impact of religion—sadly, primarily as a tool of division and harm. In contrast, Archbishop Tutu used religion for healing and hope. He acknowledged the history of harm, stating, “When the missionaries came to Africa, they had the Bible and we had the land. They said ‘Let us pray.’ We closed our eyes. When we opened them, we had the Bible and they had the land.”

Yet, in his anti-apartheid work, Tutu used the Bible’s principles to pursue a return to justice. After the initial dismantling of apartheid, even amidst the remaining devastation, Tutu reclaimed the biblical metaphor of the rainbow. He proposed that South Africa be called the Rainbow Nation, a symbol of the hope that comes in the unity of diversity.

The murky streams of racism still affect every aspect of South Africa. And, as our travels newly reveal, myriad forms of bigotry flood our world with inequality and injustice. Certainly, our home country has its own legacy of apartheid (i.e., segregation)—and lacks South Africa’s explicit efforts toward restorative justice. Yet, the rainbow of stories that recognize injustice, pursue peace, and raise hope create an arc that bends toward Ubuntu.